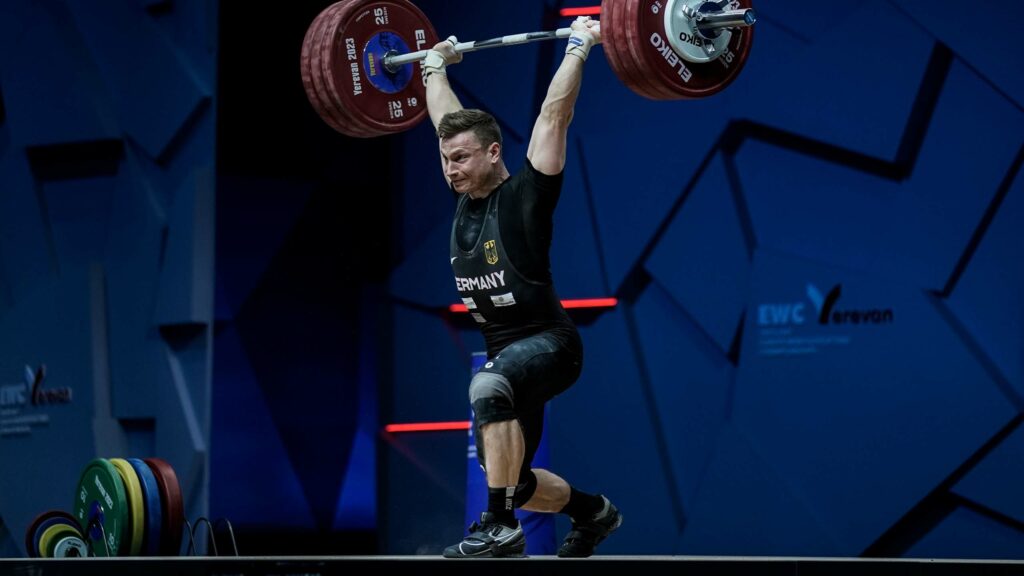

The nose runs, a scratching in the throat. Who does not know this? Acute diseases can have far-reaching consequences in competitive sports. When you work towards an Olympic final for four years, everything is designed to deliver maximum performance on that day. And an acute illness can make this goal much more difficult. There are many internal and external factors associated with acute diseases. Currently, we find evidence that increased training and competition stress as well as increased psychosocial stress are crucial for the development of acute diseases.

ACUTE DISEASES IN COMPETITIVE SPORTS

An acute illness represents a serious health burden for the athletes. This can result in reduced performance, an interruption in training or even the failure to participate in important international competitions. Among British athletes it has been documented that 33% of missed training sessions are due to acute illnesses.1

An analysis of large international competitions and tournaments showed that 6-17% of the athletes* had acute illnesses during the tournament period.2, 3, 4, 5The numbers continued to rise when the competition period lasted longer than 4 weeks. Acute infectious diseases can affect several organ systems. Besides the digestive tract, the skin and the urogenital tract, the respiratory tract is particularly affected. Just these illnesses of the respiratory tract can additionally increase the risk for more serious medical complications. 6

But what then leads to a decrease in training and competition performance? Decisive factors here are impaired muscular coordination, a decrease in muscle strength, a decrease in maximum oxygen intake and changes in metabolic functions. In addition, the occurrence of fever can affect the body’s temperature regulation, resulting in increased fluid loss. Less fluid also means that the stroke volume of the heart decreases. 7

A MULTIFACTORIAL PROBLEM

Is the training and competition stress related to the occurrence of acute diseases? When we think about it, it seems relatively clear to say that a high and intensive training load increases the risk.8 It is also understandable that a very low training load or no training at all can lead to acute diseases. Therefore, a moderate training load is probably best to compensate for.9 This is definitely true for hobby athletes* with national competition experience.

It becomes interesting when observing international elite athletes. This shows that even high and intensive training loads are accompanied by a rather low risk of acute diseases.10 How is this possible? Well, we have no answer yet. However, it is clear that in order to reach the top of the world, we need an excellent physique and an outstanding immune system in order to withstand the physical and psychological stress.

Australian football players were also shown the importance of sleep on physical health. During the examinations, the duration of sleep was also documented. Significantly lower sleep times led to clinical symptoms in the athletes within 7 days.11

The occurrence of acute diseases in competitive sports can therefore not be clearly attributed to individual factors. It is a multifactorial problem and must be treated as such. Here, stress and recovery stand opposite each other as if on a pair of scales. If an imbalance occurs, the scale tilts and the clinical condition may deteriorate. However, this is only valid for one athlete and cannot be generally applied to the sport. The load management must always be individually adapted.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

The prevention of acute illnesses is an important part of the athlete’s athletic health in order to minimize the loss of training and to be able to achieve maximum performance during important competitions. The prevention program of the Norwegian Olympic team was able to reduce the illness rate from 17.3% in Turin 2006 to 5.1% in Vancouver 2010, which led to a significant improvement in the performance of the entire team. For comparison 19 medals, including 2 gold in Turin 2006 and 23 medals, including 9 gold in Vancouver 2010.12

There is no one-size-fits-all method to completely reduce the risk of acute illness, but we do have a variety of behavioral, nutritional and medical intervention strategies. The athlete together with his coaching team is responsible for developing these strategies, integrating them into the training process and then controlling them.

We need to understand which factors negatively influence our health and which factors positively influence it. Only in this way can specific measures be developed to effectively minimize the risk of acute diseases.

Resourves

1) English Institute of Sport, 2009. Injury and Illness in Great Britain Sport. Olympiad review, 2009

2) Engebretsen L, Soligard T, Steffen K, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses during the London Summer Olympic Games 2012. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:407–14.

3) Soligard T, Steffen K, Palmer-Green D, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses in the Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:441–7.

4) Engebretsen L, Steffen K, Alonso JM, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses during the Winter Olympic Games 2010. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:772–80.

5) Ruedl G, Schobersberger W, Pocecco E, et al. Sport injuries and illnesses during the first Winter Youth Olympic Games 2012 in Innsbruck, Austria. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:1030–7.

6) Schwellnus MP, Jeans A, Motaung S, et al. Exercise and infections. In: Schwellnus MP, ed. The Olympic textbook of medicine in sport. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008:344–64.

7) Weidner TG, Sevier TL. Sport, exercise, and the common cold. J Athl Train 1996;31:154–9.

8) Matthews CE, Ockene IS, Freedson PS, et al. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and risk of upper-respiratory tract infection. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:1242–8.

9) Nieman DC, Henson DA, Austin MD, et al. Upper respiratory tract infection is reduced in physically fit and active adults. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:987–92.

10) Malm C. Susceptibility to infections in elite athletes: the S-curve. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2006;16:4–6.

11) Dominic Fitzgerald, Christopher Beckmans, David Joyce, Kathryn Mills. The influence of sleep and training load on illness in nationally competitive male Australian Football athletes: A cohort study over one season, 2018

11) Hanstad DV, Ronsen O, Andersen SS, et al. Fit for the fight? Illnesses in the Norwegian team in the Vancouver Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:571–5.